I shall lead you into some territories you’ll find hard to swallow. One of these is the acceptance of one’s “weaknesses” and the idea that weakness is the inevitable counterpart of strength. This is a view that is alien to our scientific-industrial society, which admits only to perfection. If you have weaknesses, the traditional view is to send you to school to correct them. As a consequence, engineers are berated because they write poorly, artists shamed because they are disorderly, and administrators accused of lacking imagination. All this is unfortunate and blind to human nature. The qualities criticised are innate, a consequence of the dichotomous organisation of the mind. Walter Lowen

The level of motivation or the degree of stress you experience is directly related to your ability to "live" your priority values. When you are unable to live your priority values it is because you lack either the skills, support systems, or both. Skills fall into four basic categories:

- Instrumental - tools/hands

- Interpersonal - communications

- Imaginal - creative

- System - making connections/seeing the bigger picture

- Peer - people outside your workplace engaged in similar work to yourself, with whom you can share regularly.

- Work - people in your workplace who give you sustained positive support and you do likewise with them.

- Intimacy - someone to mutually share with at depth on a regular basis.

- Resource - access, as required, to the appropriate mix of skills, abilities and other resources.

It is not a good idea to get peer, work and intimacy support from the same person or group of people. Keep these three support systems separate from each other.

Note: Many values will require one or more of the support systems to be in place in order that you can give full expression to those values in your life.

Through categorising the skills needed to live each of the 128 values, it's possible to produce a chart from your priority values:

|

| Figure 1. Skills Needs--Determined from Priority Values |

The person, from whose values the above chart was derived, will need mainly interpersonal and system skills to effectively live their priority values.

In the Minessence Values Framework [MVF], growth is more about how you live your values, rather than about living a preferred (according to whom?) set of values. In the MVF, skills, along with challenge, play a very important role in personal growth and development for growth is defined as continually increasing one's level of sophistication (complexity of skill) in living one's values.

Skills & Complexity

A complex world is what we are familiar with. Complexity is normal. It is something we have grown to respect. We stand in awe of nature’s complexity, from the function of the human body to the incomprehensible marvels of microscopic particles. This reverence for complexity has led us to develop our own complex machinery and intricate social support structures. We fail when we confuse “complexity” with “complication”. To messy minds, complicated things are much easier to construct than complex orderly structures. [Nader 1999, pp. 331-332]

It seems that we have been genetically programmed over the past million or so years to seek happiness. It turns out this is no accident, it is necessary for our ongoing survival as a species. The upshot of this genetic programming is that, through our endeavours to do things so we feel good, we each become more and more sophisticated (more complex) beings.

Complexity may be the answer to the age old question, “What is the meaning of life?” the answer being, “To decrease entropy—i.e. increase complexity—in the universe.” The arrow of progress and growth points in the direction increased complexity. It is not surprising, then, that we are genetically programmed to only be happy when we engage in activities that lead to increased complexity.

Csikszentmihalyi (1998, pp. 74-75) describes activities that lead to happiness as flow activities. He believes there is a strong link between flow experiences and the increased complexity of consciousness:

In our studies, we found that every flow activity, whether it involved competition, chance, or any other dimension of experience, had this in common: it provided a sense of self discovery, a creative feeling of transporting the person to higher levels of performance, and led to previously undreamed-of states of consciousness. In short, it transformed the self by making it more complex. In this growth of self lies the key to flow activities.

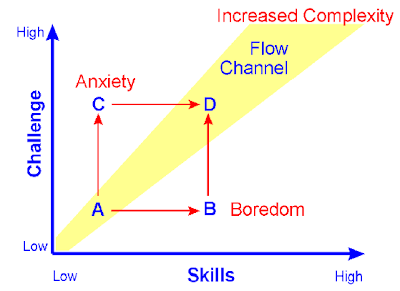

A simple diagram might help explain why this should be the case. Let us assume that Figure 24 represents a specific activity—for example, the game of tennis. The two theoretically most important dimensions of the experience, challenges and skills, are the diagram's axes. The letter A represents Alex, a boy who is learning to play tennis. The diagram shows Alex at four different points in time. When he first starts playing (A), Alex has practically no skills, and the only challenge he faces is hitting the ball over the net. This is not a very difficult feat, but Alex is likely to enjoy it because the difficulty is just right for his rudimentary skills. So at this point he will probably be in flow. But he cannot stay there long. After a while, if he keeps practising, his skills are bound to improve, and then he will grow bored just batting the ball over the net (B). Or it might happen that he meets a more practised opponent, in which case he will realize that there are much harder challenges for him than just lobbing the ball—at that point, he will feel some anxiety (C) concerning his poor performance.

Neither boredom nor anxiety are positive experiences, Alex will be motivated to return to the flow state. How is he to do it? Glancing again at the diagram, we see that if he is bored (B) and wishes to be in flow again, Alex has essentially only one choice: to increase the challenges he is facing. (He also has a second choice, which is to give up tennis altogether—in which case A would simply disappear from the diagram.) By setting himself a new and more difficult goal that matches his skills—for instance, to beat an opponent just a little more advanced than he is—Alex would be back in flow (D).

If Alex is anxious (C), the way back to flow requires that he he could also reduce the challenges he is facing, and thus return to flow where he started (in A), but in practice it is difficult to ignore challenges once one is aware they exist.

The diagram [Figure 2] shows that both A and D represent situations in which Alex is in flow. Although each are equally enjoyable, the two states are quite different in that D is a more complex experience than A. It is more complex because it involves greater challenges, and demands greater skills from the player.

|

| Figure 2. Increased Complexity = Personal Growth |

But D, although complex and enjoyable, does not represent a stable situation, either. As Alex keeps playing, either he will become bored by the stale opportunities he finds at that level, or he will become anxious and frustrated by his relatively low ability. So the motivation to enjoy himself again will push him to get back in the flow channel, but now at a level of complexity even higher than D.

It is this dynamic feature that explains why flow activities lead to growth and discovery. One cannot enjoy doing the same thing at the same level for long. We grow either bored or frustrated; and then the desire to enjoy ourselves again pushes us to stretch our skills, or to discover new opportunities for using them.

In the video below, Csikszentmihalyi gives a more comprehensive explanation of this process.

Tying this all together. The person depicted in Figure 1, to live a happy, meaningful, fulfilling life, must take on ever more challenge in relation to interpersonal and system skills, with a commensurate increase in interpersonal and system skill levels.

![Minessence Values Framework [MVF] Knowledge-Base](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhIGScgCQgcruG9D-BnG5VcP0WdUF57YKjMuNJiXFZiXkMKg8GYV_XvWD0Wmo-q2hY216ifrtriYpOvkLLSIJSpVvhrrVM4ZQmeQsEJ8B5dpRAXNdu2SRjubna6oJ8faq224iCBTg2BPoCS/s1600/KBBannerNTP.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment